Alma Miranda was excited about landing a job at a company with a reputation as a great place for women to work. Her enthusiasm deflated quickly.

Miranda started as an accountant at North Chicago-based pharmaceutical firm AbbVie Inc. right as the pandemic hit the U.S. last spring, and was quickly thrust into juggling her new paying job with an unpaid position as de facto teacher to her three young children. Miranda says her bosses piled on assignments and ignored her requests for a slower pace until she could adjust to her dual identity. “It was just too much between the job and then the schooling, the cooking, the cleaning, the laundry,” Miranda says. “I was working 12 hours a day.”

She quit her job in May and opted not to seek another so she can help her children with their schoolwork. “It’s just easier this way,” she explains, adding that her husband is an essential worker who hasn’t been able to help much at home.

In a statement, AbbVie said it was committed to an environment that allows for success. To help achieve that goal, it offers flexibility that allows employees and managers to determine when, where and how the work is accomplished.

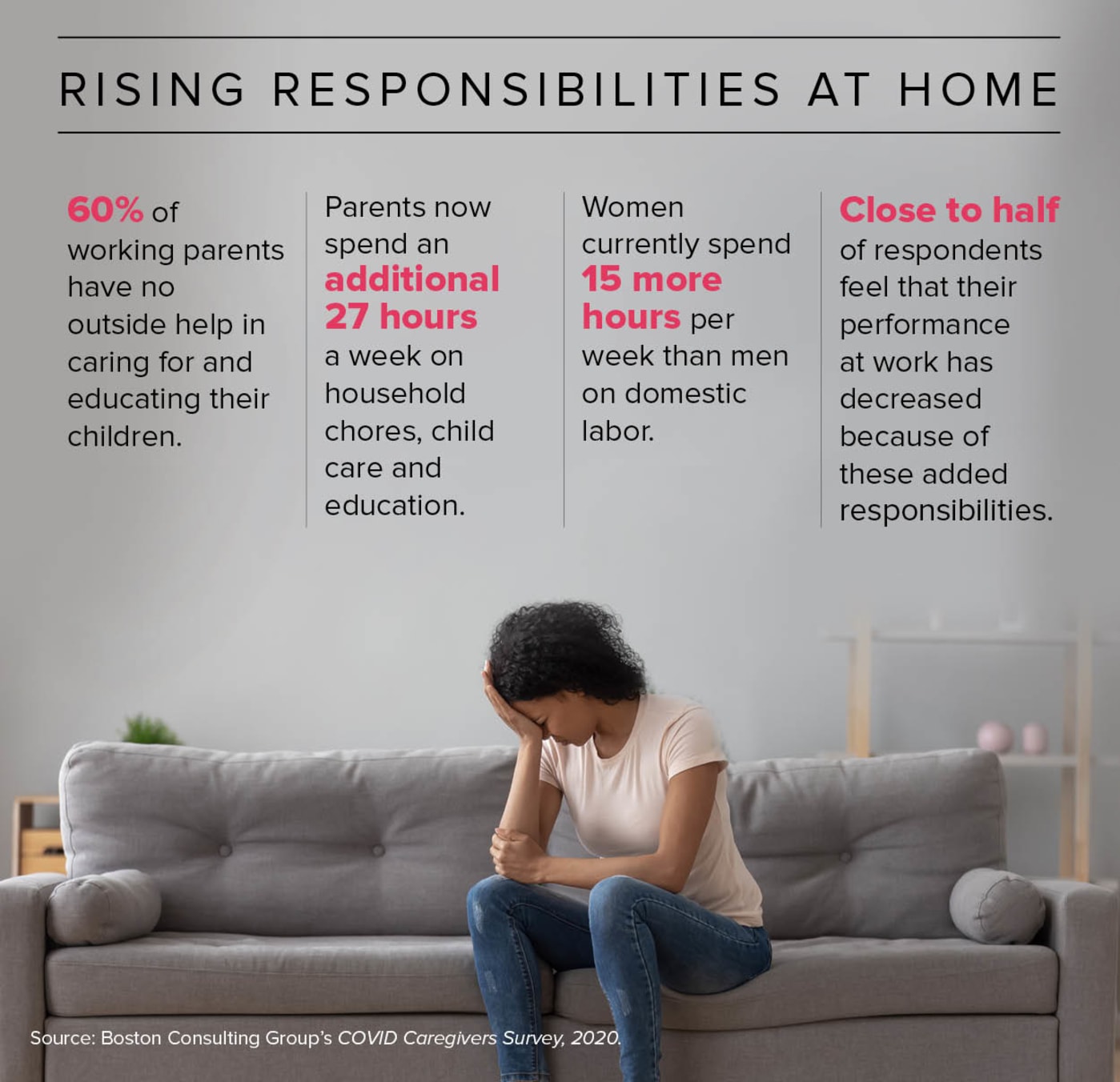

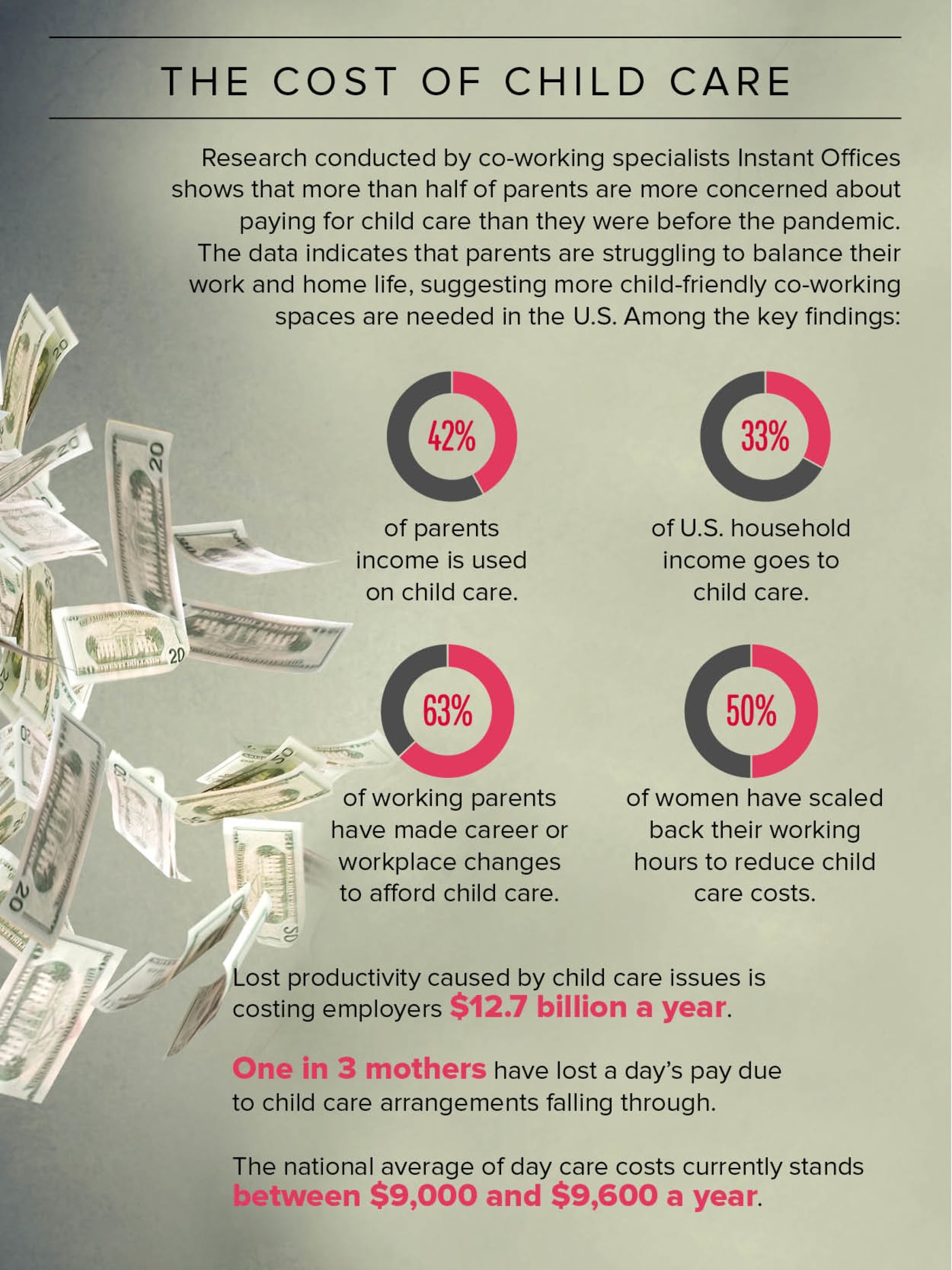

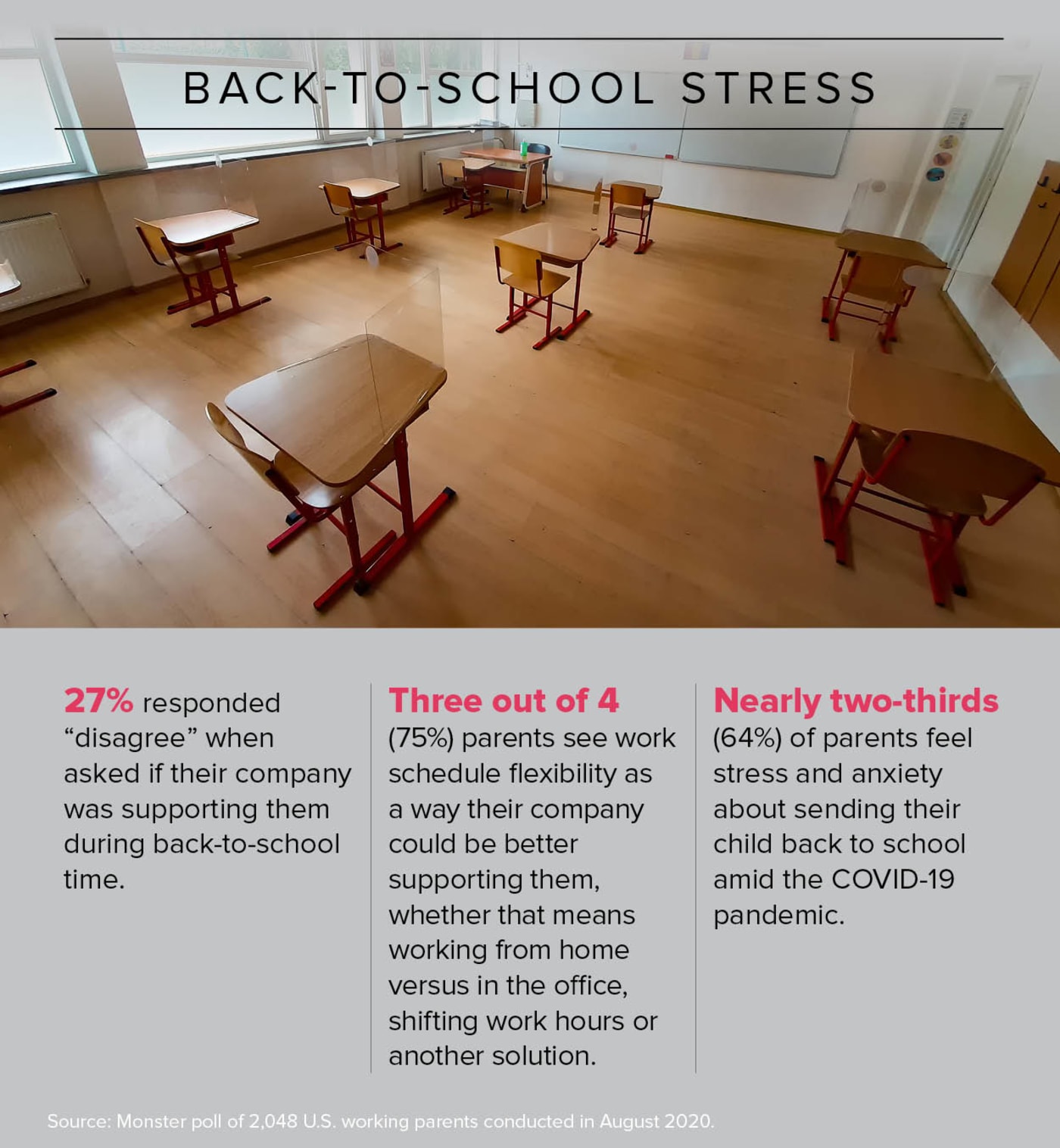

Flexible scheduling has become a common practice at most companies as the pandemic drags on, keeping physical schools and day care centers closed in many parts of the country. Employers are authorizing workers to create work schedules that will permit them to fulfill their job responsibilities while addressing family needs. Study after study shows, however, that women are shouldering more of the domestic and child care responsibilities. That means they’re on a virtual high-wire act that requires getting up early in the morning and going to bed late at night to complete the work they’re paid for so they can tend to their children during the day.

The resulting exhaustion has led many women to quit or scale back their hours. Those who don’t have that option—such as single mothers—worry about their job performance and how it may affect their career paths. Women still make 81 cents for every dollar earned by men, according to PayScale, and women of color earn 75 cents. Experts worry that the pandemic is destroying the strides women have made in the workforce and will put equity further out of reach.

Flexible Hours No Longer Enough

“There’s no wishing this pandemic away. If employers don’t come to terms with this [crisis], we will come out [of this] a workforce bleached of mothers,” says Joan Williams, a law professor at University of California-Hastings and director of its Center for Worklife Law.

In 55 percent of U.S. households, women are twice as likely to have primary or sole responsibility for cooking, cleaning, child care and education during the pandemic, according to a survey by Boston Consulting Group. Women are spending 15 more hours a week on domestic labor than men—equivalent to a day and a half.

Stopgap measures to get through the spring and summer, such as flexible work hours, won’t suffice much longer. “People are reaching a breaking point,” says Pam Cohen, president of WerkLabs, the research division of The Mom Project, a Chicago-based company that provides job-placement services and other support for mothers in the workplace. “They aren’t seeing a finish line. It’s like a never-ending ultra marathon.”

One upside of the pandemic, experts say, is that skeptical employers learned that people can work from home and be productive. The next step is for companies to add child care benefits and truly embrace job sharing and part-time work for career-track positions. “We need new work structures,” Cohen says.

Support Systems

Some organizations, especially larger ones, are stepping up to the challenge. Tech behemoths Google, Facebook and Microsoft are among the companies that have added more paid leave to accommodate employees. Analog Devices Inc., a tech company based in Norwood, Mass., and Synchrony Financial, a financial services firm in Stamford, Conn., hosted virtual activities for children over the summer and are now adding elements such as tutoring for the fall. Cisco Systems Inc., a San Jose-based tech giant, is creating a special hybrid school/activity center where employees can leave their children while they work.

“We’re still figuring out what to do,” says Sylvia Mahlebjian, senior director of learning and leadership development at Analog Devices, adding that companies are facing an unprecedented landscape and Analog wants to ensure that it wisely spends its resources.

The situation has triggered more conversations at Analog about addressing the needs of its female employees. “We have been working one way for so long,” Mahlebjian says. Meanwhile, managers are being told “to focus on outcomes, not hours,” she adds.

Career Concerns

The hours for many working mothers are exceedingly long, however. TraLiza King, an Atlanta-based director in PwC’s tax department, says the interruptions from her two daughters drag out the workday as she stops and starts her projects to deal with their requests. “I’m exhausted to say the least,” says King, a single mom who is also caring for her mother. She says that “having no support with the kids is just a different beast.” King worries that her need for flexible time might dampen her career prospects, even though her boss has been very understanding about her plight. She fears that management may not want to burden her with additional responsibilities. “I make sure I’m checking in with her to let her know what’s going on,” King says. “You have to be a better version of yourself.”

Miranda Davis was extremely unhappy with the iteration of herself that was emerging as she tried to educate her two sons while working as project manager at an educational publisher. “I was screaming at the kids,” says Davis, who requested her employer’s name not be used. “I was feeling disgruntled at work.”

Davis says her employer was fine with letting her work at home but that “no one was discussing how the workload is getting done if you aren’t able get to it in daytime hours.” She eventually took a six-week leave and started to work part time in July. “Something had to happen; otherwise, I was going to have a breakdown,” she explains, noting that her husband doesn’t have the option to work from home. The promotion she was discussing with her boss before the pandemic has been put on hold.

Working part time is going well, though Davis finds herself addressing business needs on her off-hours. “I sometimes wonder if it’s really worth it,” she says.

A Helping Hand

Experts share the following tips on how companies can best help women (and men) who are working from home while also caring for their children:

- Communicate openly and frequently with your employees. Listen to their needs and concerns and be as accommodating as possible.

- Remind employees of your mental health benefits and bolster them if feasible.

- Encourage workers to take their vacation or paid time off, and make sure managers understand the importance of allowing time away from work.

- Promote the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which requires certain employers to provide their workers with paid sick leave or expanded family and medical leave for reasons specifically related to COVID-19.

- Set standards for work/life balance. For example, instruct managers and supervisors not to send nonurgent e-mails at all hours and don’t expect immediate responses to questions that can wait.

- Prioritize which employee projects are most important so workers know where to focus.

- Explore paying for or subsidizing virtual or in-person tutoring services or babysitting.

- Consider introducing job sharing or part-time work for positions where those options don’t exist.

- Reduce the number of meetings and carefully choose who must attend.

- Record meetings or have someone take notes for those who can’t attend.

- Take employees’ overall record into account in performance reviews, raises and bonuses. Right now, employees are navigating challenging circumstances. —T.A.

Mothers File Lawsuits

Some mothers—notably single moms and those who otherwise support their families—can’t pare back their hours, and their employers’ alleged inflexibility is resulting in lawsuits. Drisana Rios of San Diego sued her former employer, insurance brokerage HUB International, for gender discrimination, harassment and wrongful termination in a suit that alleges she was fired for failing to keep her two children quiet during business calls, according to various press reports. Rios also alleged that her boss badgered her for not having child care even though day care centers were closed. Representatives from both sides didn’t return requests for comment.

Single mother Stephanie Jones, former director of revenue management at Eastern Airlines LLC, sued the company and two of its executives for allegedly firing her for requesting leave under the federal coronavirus relief law to take care of her son because his school was closed. Passed in mid-March, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) requires certain employers to provide employees with paid sick leave or expanded family and medical leave for specific reasons related to COVID-19. In response to Jones’ request, one of the executives wrote in an e-mail that the new laws were there as “a safety net and not a hammer to force management into making decisions, which may not be in the best interest of the company or yourself.”

Jones says she was working from 5 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. with few breaks as the Wayne, Pa.-based company shifted its strategy to provide repatriation flights for those stranded outside of the U.S. amid the pandemic. That meant she couldn’t help her son with his schoolwork when he asked.

“It made me feel like a failure as a mother that I didn’t have the time to help him during the transition,” Jones says. “We also had connectivity issues. We couldn’t get into lesson plans.”

Jones requested to work from home and have two hours a day to help her son. She was expecting to discuss it with a company official on March 27 but instead was fired for unspecified “conflicts,” she says. The company has also alleged that the FFCRA wasn’t in effect when the leave request was made, according to Jones’ lawyer, M. Frances Ryan, who denies that claim. Eastern’s lawyer declined comment and company representatives didn’t return requests for comment.

New Initiatives

Cisco Systems is taking a big step to ease the pressure on its working parents. In late August, it started an onsite, all-day program for employees’ children, from kindergarteners to 12-year-olds. The company isn’t developing any curriculum but hired teachers to help students with their remote learning as well as keep them occupied after the school day ends.

“When we realized schools in the Bay Area weren’t going to reopen, we said, ‘What can we do?’ ” says Katelyn Johnson, senior manager of global benefits at Cisco. “Parents, particularly women, because they do carry more of the load, were not going to neglect children’s physical, emotional or academic needs.”

The company had a head start on developing safety protocols because its onsite day care centers, which accept infants to 6-year-olds, were open for first responders. There are daily temperature checks, and masks and social distancing are required. Children are assigned to small groups with a dedicated teacher, and there isn’t any intermingling to limit infection risk. Parents are not allowed in the center.

Cisco is exploring other benefits, too, such as providing private tutors or hiring a teacher to instruct a small group of children in what are known as learning pods, pandemic pods or micro schools. The concept has become popular in affluent neighborhoods throughout the country where parents hire tutors to teach their children or band together with other families to form small classes. Pods eliminate the risk of being in a large group and provide children with more attention and guidance than virtual classes, according to advocates.

The pods have also been called out as a symbol of the income inequity that the pandemic has laid bare. Rich families can hire tutors, buy the latest technology and renovate their homes to create distinct learning spaces. Children from lower-income families may lack reliable Internet connections, up-to-date computers and a quiet place to learn.

Synchrony is exploring that dichotomy as it develops strategies for its working families, including the roughly 10,500 employees that work at its call centers, many of whom are women. Liz Heitner, the company’s senior vice president for talent and transformation, says that while call center workers are paid fairly, Synchrony worries that some of the employees’ children may lack the essentials they need for school.

“We are away of the digital divide,” Heitner says. Synchrony gave about 400 Chromebooks to employees based on their needs. It also expanded its backup childcare and mental health benefits.

“This is one of the most stressful times to be a working mother,” Heitner says.

For Some Women, the Challenge Is Finding Work

As many working mothers struggle to find a balance between career and family, other women are simply desperate to land a job. Overall, working women—especially those of color—have endured a higher unemployment rate than men since the pandemic hit the U.S. in the spring. In August, the unemployment rate for women was 8.4 percent compared with 8 percent for men, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The rates for Black and Hispanic women were 12 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively.

That’s actually an improvement over earlier in the year: In April, the overall rate for women was 15.5 percent (for men it was 13 percent); for Black women the rate was 16.4 percent and for Hispanic women it was 20.2 percent.

There are several reasons for the gender difference, according to experts. One is that more women are quitting their jobs to stay home and take care of their families because schools and day care centers remain closed in many parts of the country. And while one bright spot of the pandemic is that it convinced many skeptics that employees could be productive working from home, women are widely employed in industries such as hospitality and caregiving where remote work isn’t possible.

“There’s no silver lining if you can’t work from home,” says Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. Gould adds that women make up a large segment of government employees and could be at risk if there are widespread public-sector layoffs.

Charissa Ward was furloughed from her position as a server at Walt Disney World in April and hasn’t been called back, even though the theme park reopened at a limited capacity this summer. The mother of three was her family’s primary breadwinner and doesn’t know how she’ll find another job when there are scant openings for waitstaff and so many other servers are out of work. Alternate job options are limited, and Ward has worked as a server for 15 years and doesn’t have any recent experience doing anything else.

“I’m not against trying new things,” she says, “but you’re competing against so many other people.”

On some days, Ward admits, “I just feel hopeless.” Yet she acknowledges that her family is better off than many. They have savings, though they have plowed through half of their reserves already. Her partner has a job, and her colleagues held a school supply drive, which helped outfit her children as they started classes.

It’s still a struggle: Ward says she has visited food banks to help the family stretch its dollar as they cut back on spending. And the future remains uncertain. Even if Ward is called back to work, her salary won’t return to pre-pandemic levels. “We worry,” she says. “How much longer can this situation go on?” —T.A.